Dr. Adam Hammer, who I believe is the founder of the Bavarian Brewery (precursor to Anheuser-Busch), was my belief. His life was fascinating before he started the business that would one day become a global brewing giant.

Although not all German immigrants to St. Louis were refugees from the revolutions in Germany’s past, Adam Hammer believed that fleeing from imprisonment and prosecution was what drove him to move to the United States. While many early St. Louis brewers were not interested in politics, Hammer is directly connected to both the European and American progressive movements of the 1840s-1850s. He made important discoveries about heart disease and revolutionized medicine in St. Louis, America, and returned to Germany to make political contributions. His business interests laid the foundations of the largest multinational brewery corporation in the world, in addition to all of these accomplishments, each of them is worthy of fame.

Hammer was only a few years after Napoleon’s defeat in 1818 and was born in Mingelsheim. It was part of the Grand Duchy of Baden. This was the last German state to retain its independence. The Grand Duchy of Baden was only one of the few to join the Prussian-dominated empire in 1871. The young Hammer was a graduate of the University of Heidelberg and studied literature, natural science, and mathematics. After graduating from the university’s medical school, he began his professional career in Mannheim. But the revolution was calling and Dr. Hammer became a politician in 1847 after the Sonderbund War in Switzerland. His first attempt to fight for greater representative democracy was a failure. He fled to St. Louis with Friedrich Hecker, fearing the wrathful Prussian King Frederick William IV who had suppressed their revolt in Mannheim.

Germany’s democracy would need to wait.

Hammer was a private practitioner in St. Louis by 1850. The federal census from that year gives a wealth of information about Hammer and his brothers who also settled in St. Louis. Hammer was 32 years old and working as a doctor; Charles, his brother, was 25 and working as a “soda maker” while Philip, 20 was not listed. Elizabeth Kritz (20 years old) was also listed as living with the household. She may have been a servant. Helena, Adam’s wife, was not listed. However, I found a legal agreement bearing their names that sold a Soulard Vinegar factory and its whiskey barrels to John Wm for $550. Haeckel was an early business partner for Adam Lemp. It seems that land speculation was a popular way to invest money. Two years later, Eberhard Anheuser bought a plot for $800. Hammer would then return to the role he played in this sale.

Hammer’s attention was instead on St. Louis’ medical profession, which Hammer described as a little less than professional before the arrival of German doctors. When the public saw the shocking disposal of cadavers at two of the city’s medical colleges, there was a day of riots. One encomium on German medicine.

“…The American people owe them an inexorable debt of gratitude for their pioneering work in medicine and surgery, as well as for inspiring true medical learning …”

Hammer’s first venture into formal medical education was in 1855 when he founded the St. Louis College of Natural Sciences and Medicine. Hammer’s proposed curriculum was different from other medical “colleges”. It offered a wide range of courses in epidemiology and anatomy. At a time when medical school training only lasts four months, it was more than 18 years. Unfortunately, the school was closed one year later because Hammer’s professors from Germany couldn’t immigrate to St. Louis. Hammer would always keep the dream of a medical school in his mind.

The doctor was already well-known in the German-American society, which gathered along South Second Street. There, the aroma of hops from George Schneider’s and Adam Lemp’s breweries could be detected in the air. Hammer was highly respected and well-known for his charismatic personality. Ernst Kargau would recount this story in The German Element of St. Louis.

A newspaper advertisement from 1857 is just one example of Hammer’s surgical skills that were turned into philanthropy, and concern for the less fortunate residents of St. Louis. He opened The St. Louis Eye Infirmary on Elm Street, between Fourth and Fifth Streets, and advertised eye surgery, among other services, for no charge. Hammer offered lessons for free to any other doctor who wanted to see his ophthalmological procedures. Although Hammer may have had some imperfections, he was a committed philanthropist.

Hammer is however lured by the possibility of earning a living from owning a brewery in 1857. Even the most unlikely candidates to own a brewery were attracted by these times. (Heinrich Bornstein was a vegetarian and a former revolutionary who corresponded back in Europe with Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx, and other radicals. He bought the Peter Wenger Brewery because there was a tavern on the first floor that housed the Anzeiger der Westens.

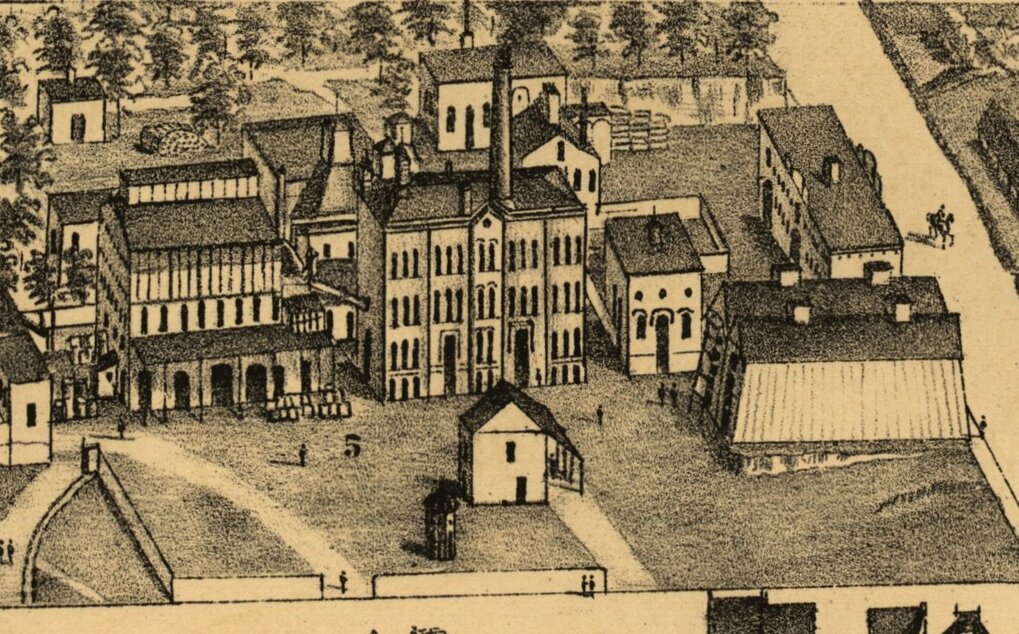

Here is where things get murky. Hammer bought the land now home to Anheuser-Busch’s famous core from an unknown rustic brewery and renovated it. There is no evidence to support this. I found no evidence of a contract between the former owners of the land, and the brewery. It is possible that Hammer raised capital to open the Bavarian Brewery in 1857. A Sunday Republican article dated 1858 lists: “Bavarian Brewery. Dr. Hammer & Co. proprietors established 1857 ….1,500 lager beer.”

According to records, Dr. Hammer did not purchase the brewery from any other person. As mentioned in Part 2, Hammer employed the brewer to run the Bavarian Brewery. It is logical that if Dr. Hammer was setting up a brewery, he would require someone to manage it. Schneider is now penniless and it seems natural that he would jump at the chance to regain his financial footing. He could use his skills to create capital for his brewery, something I doubt would be possible after his publicized failures. Karau is meticulous in his recalls and doesn’t mention Schneider owning the brewery before Hammer’s ownership.

On June 21, 1857, the Daily Missouri Republican published a report on the growing brewing industry in St. Louis. Dr. Hammer was listed as operating. According to a doctoral dissertation, Hammer advertised the form of a partnership with Dominique Urban in an advertisement published in Bornsteins’s Anzeiger des Westens on December 4, 1858. However, I couldn’t locate the advertisement and am skeptical about the dissertation’s citations of German-language newspapers.